グチック形態学 _収斂進化

GUTIC MORPHOLOGY _CONVERGENT EVOLUTION

closed on sun.mon.holidays

GALLERY HASHIMOTO

GALLERY HASHIMOTO

〒103-0004 東京都中央区東日本橋3-5-5 矢部ビル2F

かたちがいのちになるとき

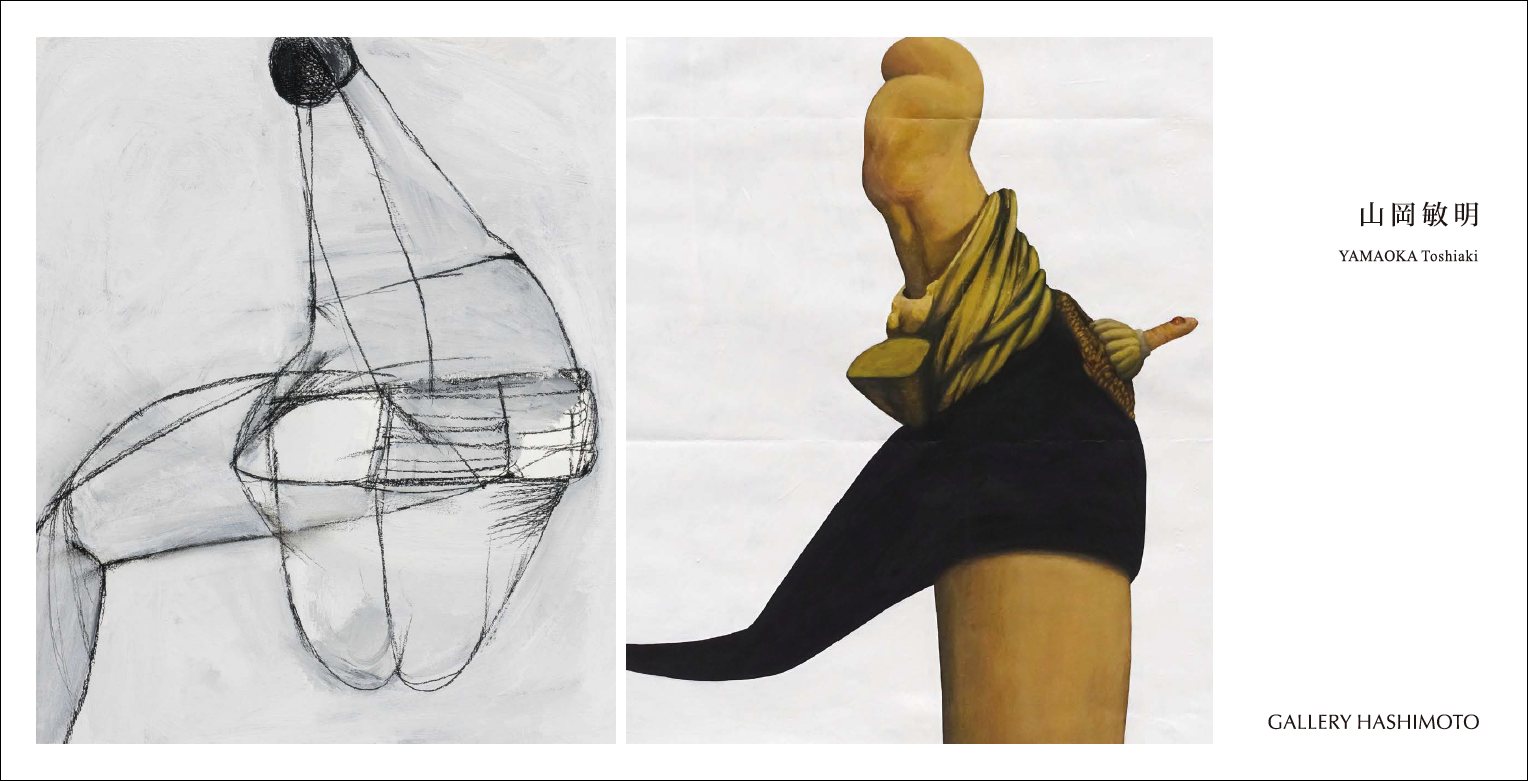

鈴木 俊晴 (豊田市美術館 学芸員 )

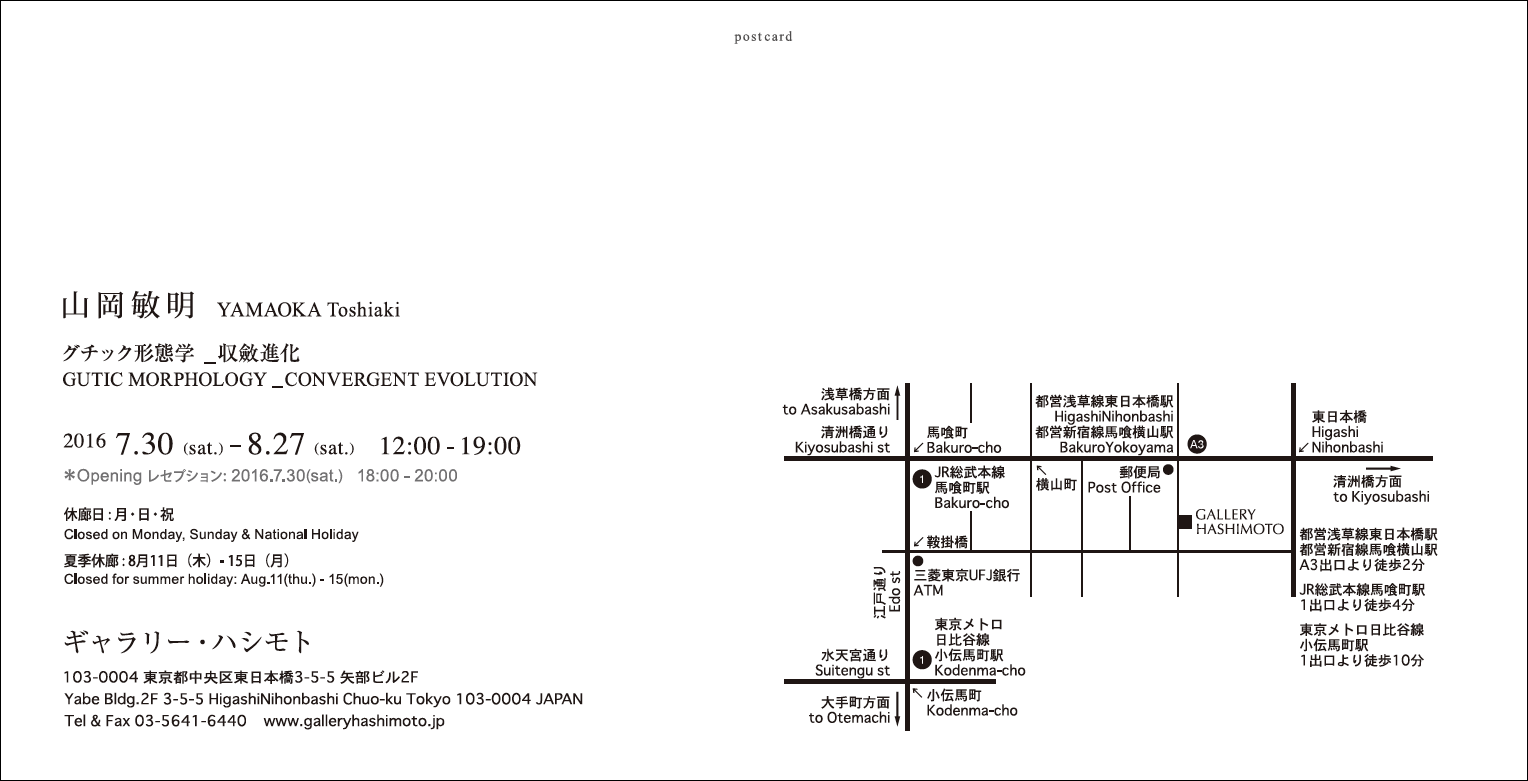

白、黒、グレーのみで描かれたそれは、しかし、異様な存在感をもって私の目を惹きつけた。存在感といっても、激しさや押しの強さとしてのそれではない。また逆の、ささやかな傷つきやすいものとしてのそれでもない。確かに生き物のようではあるが、それがいかなる生命体なのか判断しかねる。概ね重力は働いているようなので、たとえば宇宙人とは違う、せめて深海魚などのこの地上の生き物なのだろうと思わせる。とはいえ、それは同じ地上であっても、たとえばかつて私たちが想像したみたいに地球が円形の平たい大地だったとして、その周縁に私たちが認識できる生物と非生物の境があるとすると、そのギリギリ内側にとどまっている、人とも、動物とも、植物ともつかないもの。

手触りのある線描の、かたちを確定する輪郭線や、その内側を透かし見るような線によってかたどられた性器のようなもの、乳房と乳首のようなもの、樹木の節のような、植物の新芽のようなもの、そういった「のようなもの」が寄り集まって一つの存在をなしている。なしている、と断言できるのは、感覚的でしかないが、それが「なそうとしている」という断片の組み合わせではなく、一つの有機体として目の前にある感じがするからだ。さらに言えば、「のようなもの」という再現表象であれば避けられない形容を言葉ではするほかないのだが、それらは私たちの言葉の限界に過ぎず、むしろたとえば「性器のようなもの」と言ったとしても、それは描かれた生命体のなかでは、私たちには全く計り知れない別の役割を持つものとしてそこにあるのかもしれない。だから、それは厳密に言って記号ではない。むしろかたちが、私たちの目をどうしても惹きつけてしまうかたちが、意味や対象といった諸々とは無縁のままに、なかば自律的にそれそのものとしての命を宿すに至った、とでも言えそうだ。

記号から自立し、むしろそれを先導するようなかたちについて、いささか時代めくが、美術史学の泰斗アンリ・フォシヨンの言葉を引いておこう。「われわれはいつでも、かたちにそれ自身とは別の意味を探し求め、かたちの概念をなんらかの対象の表象、すなわち像(イマージュ)の概念と混合しがちである。そしてかたちの概念は、とりわけ記号の概念と混同されやすい。だが記号は〔何かを〕意味するが、他方、かたちは意味する。そして記号が見目よい形体という価値を得たそのときから、かたちは記号の重要性をしのぐ力を発揮し、記号の内実を奪い、あるいは方向を変え、それを新たなあり方へと導くのである」(*)。

山岡は子どもの頃に見た特撮ヒーローのカラータイマーや大型ロボットに入れられたスリットなど、機能性よりも造形を優先させたかのような形状に惹きつけられたという。かたちとは不思議なものだ。近代以降の美意識では、とりわけ産業デザインの分野では、かたちと機能は結びついてこそ美しい。「形態は機能に従う」(ルイス・サリヴァン)「形態は機能を喚起する」(ルイス・カーン)「美しきもののみ機能的である」(丹下健三)など枚挙にいとまがないが、機能美という言葉が端的に示すように、私たちの身体を含め、たとえその内実をうかがうことはできなくとも、外側から掴まれたかたちはそれが果たす機能に基づいてその魅力を判断される。しかし、かたちとはそのようなものだろうか。それは本来、むしろ自律した、ときとしてそれじたいで生命を持ちうるような、見る側にせよ作る側にせよ、わたしたちの理解を超えたものとしてあるのではなかろうか。

山岡は線を引き、それを擦り、天地左右を変えながら、その作業を続けていく。多少なりとも記号的なものから始まるとしても、次第にかたちは、付け加えられ、間引かれるうちに、周りにそれ以外のありえた可能性をほのめかしつつも、固有の輪郭を、それ独自の命を持ち、やがて一つの存在が絵となって現れる。そのとき、かたちは何に従っているのだろう。 少なくとも機能ではない。かたちはそんなものに縛られてはならない。 それはここでかたちそのものの命へと向かっているはずだ。かたちが生まれる切っ掛けはある。しかしそれは切っ掛けに過ぎない。

アダムは神の似姿として創造された。その男の肋骨からエヴァが造られた。それはなぜ肋骨だったのだろうかと問うても仕方ない。けれど、たとえばそれが違う骨だったら。あるいは、骨でない全く別の何かから生まれたとしたら。そうして生まれた女と男がいく世代も交わったとしたら、そこにどんなかたちの生命が生まれるだろうか。山岡の描くかたちのほとんどが画面の端で切れていることを思い出そう。それはかたちの生命がその外へとつながり、脈々と続いていることの表れに他ならない。彼の絵を見ていると、そんなことを考えたりする。大げさに聞こえるかもしれない。でも、そういうことなのだ。絵を描くということは。

(*)アンリ・フォシヨン『かたちの生命』阿部成樹訳、ちくま学芸文庫、2004年、12頁

[English Statement]

When Lives Become Forms

Suzuki Toshiharu ( Curator/ Toyota Municipal Museum of Art )

It, drawn just in white, black, and gray, captures my gaze with its outlandish sense of presence. This presence does not convey an impression of intensity or aggression, nor does it exhibit a sense of subtle vulnerability. It appears to be a living life-form, but it’s hard to tell what kind. It seems to operate according to the laws of gravity, and is therefore, I may assume, not an extraterrestrial, but a being of this world perhaps most resembling a deep-sea creature. We accept that we exist on the same planet with it. But we also see something else. By way of illustration: human beings used to believe that the Earth was a flat disc. If we imagine that around that disc there lies a recognizable boundary between living and non-living things, then we must conclude that it approaches the very edge of this boundary, but not as a human, not as an animal, not even as a plant. A drawn line with texture determines the contours of forms; another line penetrates the inside of those forms and creates other genitalia-like forms, forms like breasts and nipples, like gnarls of trees and fresh sprouts of plants, forms that assemble themselves and generate a presence. I can definitively say “generate a presence” because the forms achieve the feeling of a living organism’s presence, appearing right before my eyes, not as an accumulation of parts trying to generate a presence—although this is just my sensory impression. Furthermore, in analyzing the form, I can only use phrases such as “forms like,” which points to the limitations of our language’s capacity to depict a representation through words; even if I choose to say “forms like genitalia,” what actually exists as a part of this drawn living organism may obey a completely different function that is beyond our imagination. To be precise, what I see is not a symbol or sign. It is the form that captures our gaze, and therefore I assume that I can say that this form came to life in a semi self-sustaining way, as a being in its own right, completely independent from extraneous meanings or subjects.

Form is independent from symbol and precedes it. To quote the art historian Henri Focillon, in words some may find anachronistic: “We are always tempted to read into form a meaning other than its own, to confuse the notion of form with that of image and sign. But whereas an image implies the representation of an object, and a sign signifies an object, form only signifies itself. And whenever a sign acquires any prominent formal value, the latter has so powerful a reaction on the value of the sign as such that it is either drained of meaning or is turned from its regular course and directed toward a totally new life.” *

Yamaoka says that as a child he was intrigued by the details of characters in Japanese superhero TV shows, such as the Color Timer from Ultraman and the baroque vents and indentations of a large-scale robot like Gundam, appreciating them for their formal design rather than their function. Form is a mysterious thing. In the aesthetics of the modern period, especially in the field of industrial design, form needed to be closely associated with function in order to claim beauty. “Form follows function” (Louis Sullivan); “Forms arouse function” (Louis Kahn); “Only the beautiful can be functional” (Kenzo Tange); and so on and so forth. As the word Kinoubi (“beautility”) simply indicates, the attractiveness of a form, viewed from the exterior or “outside,” is predicated on its function, even when we don’t know what really goes on inside, as is the case with our own bodies. But is this really how we are meant to understand forms? Aren’t forms supposed to be essentially autonomous, sometimes self-generated, and therefore beyond the creator’s and also the viewer’s comprehension?

Yamaoka draws lines, rubs them off, changes their orientations, and continues to let the drawing develop. Although the beginning of the process might be more or less symbolic, the form gradually begins to claim its innate contour as lines are added and removed, while insinuating other, discarded possibilities; it comes to life and achieves its presence, emerging as a work of art in the course of time. When this happens, what principle dictates the form? We can say at least that the form does not follow function. Mere functionality cannot bind the form. It must follow the life of the form itself. There is a trigger that causes the form to be born, but it remains just a trigger.

God created Adam in his own likeness. Eve was created from one of Adam’s ribs. We can’t help but wonder why a rib was chosen. What if it had been a different bone? Or, what if Eve was created not from a bone, but from something completely different? What kind of life-forms would develop if men and women of such a radically different origin bred over generations? Let’s remember that almost all the forms that Yamaoka draws are cut off by the edge of the paper or canvas. This reflects the way that the life of the form extends beyond the edge and continues to evolve. When I look at Yamaoka’s works, it’s this process that I think about. It may sound exaggerated. But this is the essence of what it means to create a form.

* Henri Focillon, The Life of Forms in Art. Translated by Charles Beecher Hogan and George Kubler.

(Zone Books: New York, 1989), 34.